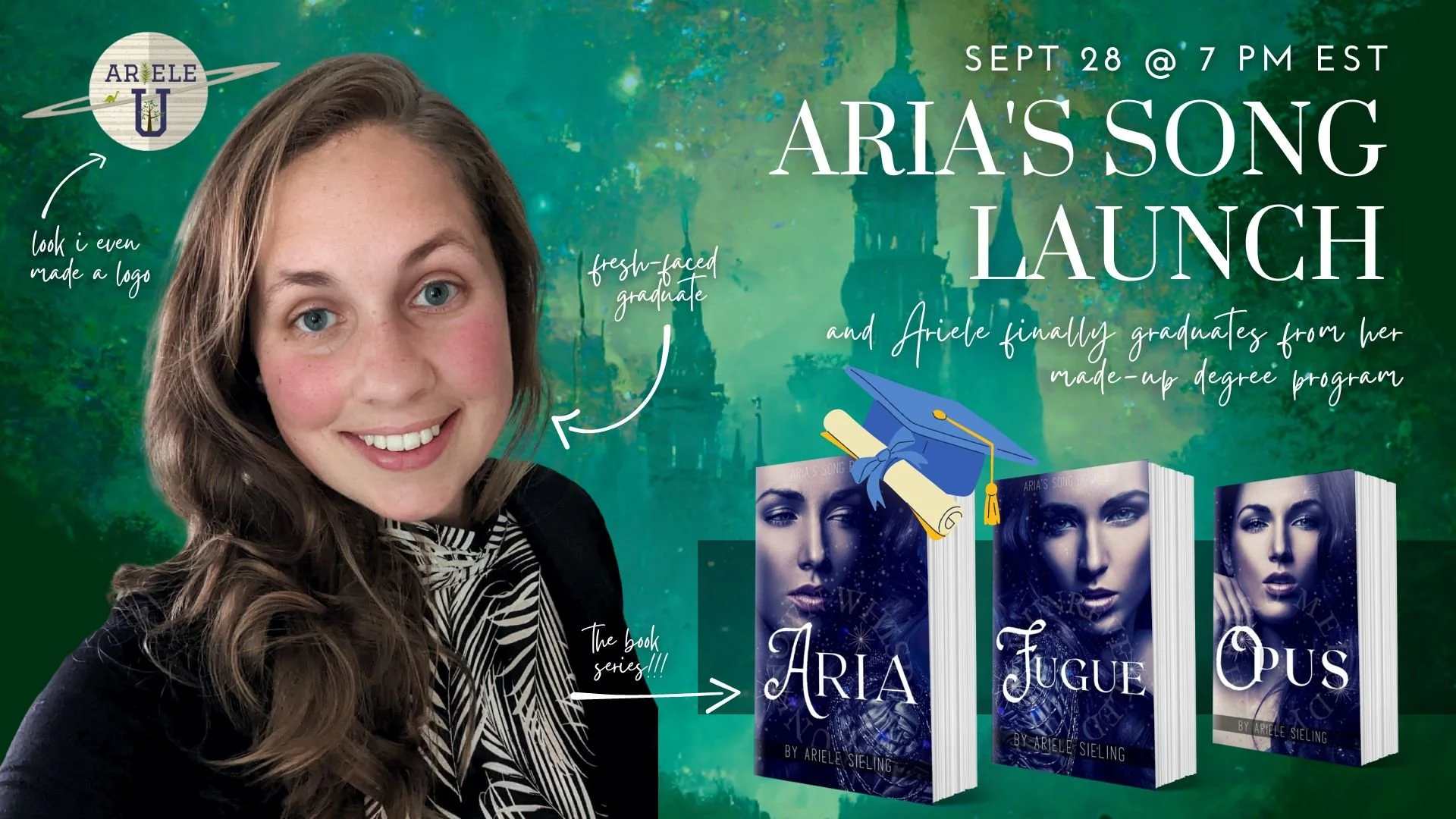

As part of my fake master’s degree thesis, I wanted to challenge myself. And one of the challenges I decided to take on was to create maps for the series.

I already do a lot of art, and I’ve sketched out rough maps before, so I decided this was a good opportunity to create a map that was good enough to put in a book.

I used a software called Krita, with a touchscreen on a laptop. I had no idea what I was doing when I started, but I messed around creating other art first, figuring out how to use the different tools included in the tool, watched a few videos on it, and then got started.

I created the background layers, then added textures and colors, and then I moved the final image to Canva, where I added the text. My first version of the map printed horribly, so I ended up selecting different fonts and making the text slightly bigger, to make it easier to read in the paperback book.

I was pleasantly surprised with how it turned out. It was challenging, certainly, and required a great deal of time and energy to create. But if I were my own professor, I’d give myself an A.

But the world map wasn’t the only one I needed. In Book 2 of the trilogy, Fugue, the main character spends a significant amount of time in a place called Thistle City (which you don’t see on the map here for reasons that are spoilers.

It didn’t even occur to me to make a map of Thistle City until I was almost ready to start the paperback design of the books. I debated not doing it, but decided it would be a good extra challenge and maybe earn me some extra credit; plus, I thought it would add to a reader’s enjoyment of the stories.

I whipped out the same software and got to work.

The second map was much easier, mostly because I knew how to use the tool, already, so I didn’t have as much figuring out to do. It was also a simpler and more straightforward map, generally speaking. Regardless, I was quite pleased with the output.

In conclusion, I would most definitely create a map for a future book or series again. It was an enjoyable process, for starters, that I think creates a better experience for a reader.

And in case you’re curious, I’ve included the black and white versions below, as they appear in the paperback editions.